Converting from Gridsome to SvelteKit

I’ll assume for the sake of this post that you’re at least a little familiar with what Svelte is. If not, I’ve written an introduction to Svelte that you might enjoy reading first before diving in here.

Otherwise: let’s dive into what SvelteKit is, how it works, why I made the choice to switch (other than the obvious fact that I just can’t resist rebuilding my site about once a year), how it’s paid off, and whether I’d make the same decisions again.

What is SvelteKit?

If you’re familiar with Next or Nuxt, it would be fair to think of SvelteKit as the Svelte equivalent.

If not: all three are “meta-frameworks,” sometimes also called app frameworks. You could think of meta-frameworks as a large set of add-ons for frontend UI frameworks like React, Vue, and Svelte (in the cases of Next, Nuxt, and SvelteKit, respectively).

If a frontend framework is a toolbox, a meta-framework is a complete workshop.

Why? Frontend UI frameworks are ideal for…well, frontend UIs. They’re built to handle pieces of an interactive user interface. By nature, being JavaScript-based, they’re limited to the capabilities of the browser page they’re loaded on. (Because of this, sites built just with a frontend framework are sometimes called “single-page applications,” or SPAs.)

A meta-framework is an enhanced toolset for building full-fledged sites and apps with a specific frontend framework (hence the “meta” part of the name; a framework for a framework).

Most meta-frameworks come with all your build tools and routing pre-configured. They also generally include data stores; layouts; image optimization; better SEO and full-page control; data fetching; and/or plugins—usually just about everything except a database to help you build anything you might want.

Going static

Next, Nuxt, and SvelteKit are all capable of building your finished project as a server-side rendered app, as a static site, or as some combination of both.

SvelteKit is even more adaptable than that, thanks to its aptly named adapters, which process your code differently for whatever type of output and hosting you’re targeting.

Currently, SvelteKit offers adapters to run your project as a Node app; as static, pre-generated HTML files; or as serverless functions (there are adapters specifically targeted for Netlify, Vercel, and Cloudflare Workers). There are several community-created adapters available as well, or you can even write your own.

This site uses SvelteKit’s static adapter, which means the pages and components are pre-rendered as plain ol’ HTML files. They can still benefit from “hydration”—JavaScript running once the page has loaded—but they don’t have to.

Thanks to the static adapter (and some strategic <noscript> tags), most of this site works just fine even with JavaScript disabled entirely.

Worth noting, however: by default, after the first page load, SvelteKit’s router hydrates and takes over page loading, to make transitions as smooth and fast as possible. You can even designate routes to preload in the background, so that by the time the user clicks, the load is nearly instantaneous.

SvelteKit layouts

SvelteKit follows the convention of layout files, which are: files that “wrap” the content of any given page in additional markup, such as a header and footer.

Your base layout file renders every route in your site or app, so you’ll most commonly use it as a base template that includes everything that would appear on every page of the site. The layout includes a <slot /> for the page’s main content to go inside, whatever that page or content might be, and SvelteKit renders the content in that slot.

Here’s what this site’s main layout file’s markup looks like (slightly simplified for readability):

<div

id="app"

class:reduce-motion={$prefersReducedMotion}

class:prefers-dark={$prefersDarkMode}

class:sidebar={pageHasSidebar}

>

<Loader loading={$isLoading}/>

<Header />

<div class="layout">

<main id="#main" tabindex="-1">

<PageHeading />

<PageTransition>

<slot />

</PageTransition>

</main>

{#if pageHasSidebar}

<Sidebar />

{/if}

</div>

<Footer />

</div>That’s pretty much it. This way, every page includes the header and footer, and the sidebar where appropriate. Some states and preferences are passed in from the global store (those prefixed with a $) so that conditional classes can be applied as needed. And the <slot /> where the page content goes is wrapped in a custom <PageTransition> component that (predictably) just adds the fancy transitions between pages.

It is possible to have nested layouts, or layouts that apply on a per-route basis. You can also reset the layout, if you have a deeply nested route that needs its own setup.

And speaking of routing…

Routing in SvelteKit

By default, a new SvelteKit project has a src/routes directory. Anything inside src/routes compiles to a page at that relative root.

For example:

| File: | Becomes route: |

|---|---|

src/routes/index.svelte |

/ (homepage) |

src/routes/about.svelte |

/about |

src/routes/blog/index.svelte |

/blog |

src/routes/blog/some-post.md |

/blog/some-post |

And so on. (Markdown files do require a small bit of extra config, but yes, you can have Markdown files as pages, or just import Markdown to inject into pages or components.)

SvelteKit can also have dynamic routes. For example, /blog/[post].svelte would be a single component that would render any /blog/* slug. You can read more about SvelteKit Pages here.

The really magical part, though, is that you can have server-side routes, too!

For example: lots of places in a typical blog need access to the list of your posts. You might want to put your most recent posts on your hompage, have some posts in the sidebar, and of course, they should all be listed the /blog page itself. You might even want category or tag pages.

That’s a lot of fetching posts to redo over and over. So it’s a perfect use case for a server-side route!

If you want your app to have a /posts endpoint that returns JSON, you just create src/routes/posts.json.js. This will become a /posts.json route in the finished application.

From there, you just define a get() JavaScript function that retrieves the desired data and returns it (along with a status code). This is made easier by the fact that SvelteKit has top-level await and fetch available by default.

Here’s a somewhat simplified example of how you might create an endpoint to return all your Markdown posts as JSON:

// posts.json.js

// The `get` function responds to GET requests; you can have post(), etc. as well

export const get = async () => {

const posts = await Promise.all(

Object.entries(import.meta.glob('/blog/posts/*.md'))

.map(async ([path, page]) => {

const { metadata } = await page()

const slug = path.split('/').pop().split('.').shift()

return { ...metadata, slug }

})

)

return {

status: 200,

body: {

posts //Automatically converted to JSON ✨

}

}

}Once you’ve retrieved the post data as JSON, you can display it in a Svelte page or component; here’s a short example:

{#each posts as post}

<article>

<img src="/images/{post.coverImage}" alt="" />

<h3>

<a href={post.slug}>

{post.title}

</a>

</h3>

<p class="excerpt">

{post.excerpt}

<a href={post.slug}>

Read more…

</a>

</p>

</article>

{/each}I won’t get too much into it here, but SvelteKit also offers a way to pre-load data server-side from routes like this, or from external sources.

Worth noting: when using the static adapter, there of course isn’t any server to query at run time. So in that case, any server-side queries or fetch calls will run at build time, and whatever the result at that point, it will be output as plain static files. Any JSON routes you might have will still be query-able on the live site, but they’ll be static.

Static SvelteKit vs. Gridsome

Before we dive into comparisons, it’s worth mentioning that SvelteKit and Gridsome aren’t exactly the same type of thing. SvelteKit is an meta-framework capable of generating many different kinds of sites and apps, where Gridsome is just a fairly straightforward static site generator.

Still, if we’re scoping the discussion to just SvelteKit’s static adapter, I think it’s a fair, if not exact, comparison.

Comparing performance

To compare Gridsome with SvelteKit, we need to do a bit of configuration. Gridsome pre-loads all of its routes in the background, so that they’re already loaded up and ready to go instantly the moment the user clicks. So unless we’re doing the same thing with SvelteKit, we’re comparing apples to oranges.

Luckily, SvelteKit does offer prefetch and prefetchRoutes functions (the former to prefetch only specified routes, and the latter to just prefetch all routes). So I threw prefetching on all the routes on the site, just to see how it would stack up against the Gridsome version.

Even when preloading all the site’s content, the SvelteKit build is dramatically smaller.

| Framework | Full size | Compressed |

|---|---|---|

| Gridsome | 3.09 MB | 1.74 MB |

| SvelteKit, preload all routes | 1.7 MB | 536 kB |

| SvelteKit, top-level routes only | 322 kB | 184 kB |

As you can see from the table above, the SvelteKit version shaves about 45% off the Gridsome build, and over two thirds when compressed. The SvelteKit site at full size is about the size the Gridsome site was compressed!

Granted, 1.7 MB is not exactly tiny, but bear in mind that’s with the weight of every route on the site preloading.

The preloading strategy I eventually settled on, however, is the last row in the table: here, I preload only top-level routes unless we’re on a blog page, and then I preload all blog routes. This was my biggest savings, but there’s a tiny caveat that I also decided to eliminate Google Analytics in this approach as well, so the reduction is slightly exaggerated. Still, though: the overall load is tiny (and honestly, mostly made up of fonts. There’s a little over 100 kB of fonts to load on any given page).

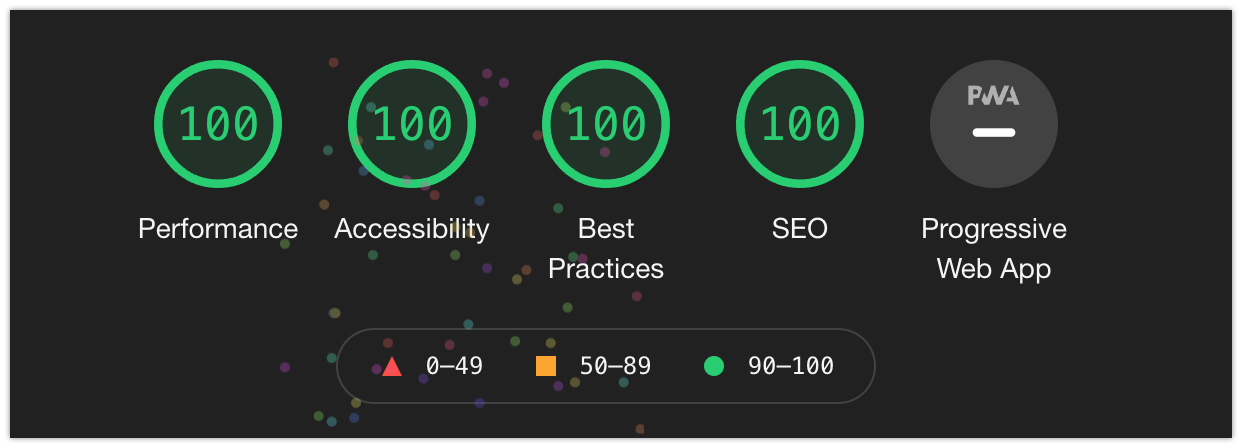

Scrapping Google Analytics was an easy decision once I realized it blocked the main thread and prevented me from ever getting an optimal performance score—even, ironically, from Google Lighthouse. I don’t really need analytics on this site, but I can use Cloudflare or even pay for Netlify Analytics for that.

By the way: although it isn’t implemented in any form in most browsers yet, I put a prefers-reduced-data media query on the site that will prevent preloading when detected.

Builds and dev start times with SvelteKit are also much faster: the production build of my Gridsome site ran about seven minutes, compared to about 90 seconds for the SvelteKit version (about five times faster). The dev startup times have similar gains. But again, this is misleading, for two reasons:

Gridsome was doing a lot of image work at build time that SvelteKit isn’t by default; and

Gridsome uses Webpack under the hood, where SvelteKit utilizes the much faster and more modern Vite (pronounced “veet”).

One particularly nice thing about Gridsome was its built-in <g-image> component. Just by using it in place of the standard HTML <img> tag, Gridsome would compress your images, generate a resized, responsive source set, use lazy loading, and create blurred placeholder images.

By contrast, out of the box, SvelteKit does…nothing to help with images.

My website uses few enough images (which are already generally compressed) that I decided browser-native lazy loading (combined with aspect-ratio) was acceptable for now. Hopefully, SvelteKit will have a first-party image compression option in the near future. (And even if not, it’s possible to rig that up directly through Vite, though that’s its own rabbit hole. Or, I could even use a service like Cloudinary if image size became an issue.) But for now, the few Svelte-focused solutions I tried didn’t work particularly well for my use case, and the tradeoff didn’t seem to be worthwhile.

Why move away from Gridsome?

As you can see from just perusing the posts list on this blog, it wasn’t all that long ago that I moved to Gridsome in the first place. I went to a headless Gridsome frontend just over a year ago, and converted the site to fully static barely seven months ago. I’ve already talked here about how nice Gridsome’s image handling is, and how fast it makes the site feel.

This naturally prompts the question: why move in the first place? At this point it almost seems like the only reason this site exists is so that I can rebuild it, then write a post about it.

I was a very early adopter of Gridsome, and at the time (in 2019), it still seemed to be regularly updated and headed towards a 1.0 release. But it’s been almost exactly two years since the last minor version update of Gridsome (0.7), and at this point, it doesn’t seem like it’s an actively maintained project any longer. It’s been all but silent since then.

Gridsome didn’t ever really feel complete to me, and that was fine when updates were still rolling out. I knew what I was in for going with a pre-1.0 technology, and it was really good at what it did well—namely, generating a speedy static site with Vue and GraphQL—but the more you wanted to tweak things or leave the happy path, the more you ran into its rough edges.

More than once, I spent a day or two fighting with NPM, unable to even run Gridsome on my machine. (That’s more to do with the packages Gridsome relies on than Gridsome itself, but still; the frustration is the same.) The last two times I’ve set up new machines, I’ve had to spend significant time trying to get Gridsome running on them. I had to explicitly set Netlify to an older version of Node to even get it to deploy.

But moreover: SvelteKit sparks joy in a way that Gridsome doesn’t anymore. It was exciting to be a part of something new and actively progressing with Gridsome, but now it just feels like being part of something forgotten and stagnant. SvelteKit replaces that feeling; the community is vibrant and the project has an electric momentum to it.

You might ask why, then, I didn’t move over to Nuxt, given that it’s a larger and energetic community. Plus, it’s still in Vue, which would seem less disruptive.

When I was writing this site in Gridsome, my list of Vue projects was fairly small, which made the appeal of having a Vue outlet more appealing. Now, though, it doesn’t feel like I need a site in Vue anymore—especially since my day job isn’t Vue-focused anymore.

Maybe the fact that I’ve been working professionally with Vue for the last two years (and released Quina late last year) is part of it, too. I still love Vue dearly, and will almost certainly pick it back up to write a project in Vue 3 one day in the near future. But silly as it sounds, for right now: that itch is scratched, and I want a different thing to play with.

This site, like any side project, is at least partially for me to enjoy. This is the one little corner of the internet that's 100% mine, where I can do anything I want for whatever reason. And that thing, right now, is SvelteKit.

Finally, TypeScript has first-class support in SvelteKit. I’m relatively new to TypeScript and have somewhat mixed feelings on it at this scope (I think it mainly shines on larger projects with multiple contributors), but I’ve been working on involving it more in my workflows to get better at it. At this point, close to 100% of this site’s JS is typed, so I’ve given it a good shot at least.

What other options were considered?

To some degree, I considered both Astro and Eleventy for this overhaul, and you could make reasonable arguments that either one would’ve been better suited for the task. If my primary goal had been to build the fastest statically generated site possible with absolutely minimal JavaScript client-side, I no doubt would’ve gravitated towards one of these tools.

In the end, however, Eleventy is still too unopinionated for my personal tastes, and Astro is still a bit too new. (Yes, SvelteKit is new, too, but it seems to have much more of a foundation beneath it.)

And again: this is my personal site, and so the tool I like the most is an important factor. So while SvelteKit might arguably be a little overkill, personally, I think it’s the most fun.

How does the code compare?

You might wonder: how does the old Vue code compare to the newer Svelte code? Is it shorter, better, and/or more readable?

Turns out: that’s actually a really tricky question to answer.

I originally thought I’d show side-by-side comparisons to demonstrate Vue vs. Svelte, but there’s been enough change at this point that most of the differences are either trivial, or so far apart they don’t even make sense to compare anymore.

The site’s changed quite a bit, even if it doesn’t necessarily look like it.

The one non-trivial component that’s mostly the same between the two versions is the font tester (seen on the /uses page). But it’s actually about the same size, both in terms of line count and disk size. The Svelte version is negligibly larger (only by a fraction of a kB), and almost certainly just because of the addition of TypeScript.

Most of the rest just isn’t comparable anymore. The colorful square grid in the header and footer has been completely refactored for better performance. TypeScript is everywhere; layouts have changed; new pieces have been added and old removed. MDSvex came with PrismJS built in, which let me delete both the a full component and an external library. Storybook and my tests are both removed for now. Lots was refactored. I relied more on global CSS previously, and have moved more towards component-based CSS this time around.

"Is it better?" is a really hard question to answer, even without getting into the highly subjective topic of what "better" even means. But I like it better (even the parts that are more verbose), and I think that's the most important part. I even enjoyed the relatively rote process of moving Vue components over to Svelte.

By the way: I kept an archival copy of the old site live for myself to look back on, just in case you’d like to compare the two for yourself.

And while we’re on the topic: here’s the link to my site’s new SvelteKit repo, if you’d like to take a firsthand look behind the scenes. A lot still needs to be refactored and cleaned up (I keep a list), but you’re welcome to poke around, or even clone the repo as a starter for your own blog if you like.

The redesign

I didn’t set out to make any design changes when moving this site over to SvelteKit, but after a while, I got tired of staring at the old design and started the dangerous journey of playing with new fonts.

In the end, the old body font (Averta Std) got promoted to the heading font, and I added a nice serif (Alkes) for the body copy. More of a small refresh than an overhaul, but the pairing and tweaked styles give the site a fresh new look that I very much like.

What to know about SvelteKit

As of this writing, SvelteKit is still in pre-1.0 status. It seems very stable to me—I don’t think anything is going to be changing—and Svelte itself is definitely solid. But there are still some portions of the Kit that aren’t fleshed out yet.

I found the static rendering to be extremely good, but as mentioned, SvelteKit can do a lot more than that. Depending on what you’re building and what features you’re most interested in, it may be worth spending some time to make sure SvelteKit is in good shape to handle your task, and works as expected with your deploy target.

Also worth knowing: Svelte itself doesn’t support IE11 by default. There are some workarounds, but hopefully that’s not anything that matters to you in the first place—especially since not only has IE11 support been dropped by a slew of major companies at this point, but it’s due to be killed by Microsoft itself in a matter of months at the time of writing.

Don’t listen to the haters

Arguments against Svelte(Kit) tend to focus on how it theoretically scales (emphasis on theoretically), and the relative size of its community and ecosystem compared to other frameworks.

I won’t go into either of those here, but I do address them both in detail in my introduction to Svelte post.

Don’t get confused by Sapper

One other thing to know at this point in SvelteKit’s existence is that it’s actually the second stab at a Svelte meta-framework; Sapper was the first.

Sapper never seemed as big as SvelteKit does now, but it’s been deprecated in favor of SvelteKit, and there’s still some confusion that arises when searching online for code solutions in the space.

SvelteKit doesn’t always work exactly the same as Svelte or Sapper by default (largely because Svelte and Sapper both have a Rollup config—Rollup being the bundler that powers Svelte—where SvelteKit has its own config file). So a lot of the examples and answers you come across related to setting up configuration are likely to either need some syntax adjustment, or just not work exactly as expected. (This doesn’t apply to Svelte itself so much as to SvelteKit and its unique configurations.)

Wrapup: would I use SvelteKit again?

For just about any project, yes, I would use SvelteKit again in a heartbeat.

Even though it’s still technically pre-1.0, SvelteKit feels very solid—much more so than other pre-1.0 frameworks I’ve tried—and it’s a delight to work with. The adapters allow you to tailor your input to any output you like, and the scope of things you can build with it is impressively vast. Plus, it’s likely to be smaller and faster than whatever else you might have chosen, and with even better developer experience.

As mentioned, it’s still early days for SvelteKit, so there are still some areas where its established solutions may not be as robust as with other frameworks. I can understand hesitance to bet the farm on something a little newer, but I don’t think I’d have any real hesitation at this point. An established solution with a rich ecosystem like Nuxt might have more to offer in this moment, but I’m confident both that I could do anything I needed to do in SvelteKit, and that it won’t be long before SvelteKit fills the gaps. It’s hard to imagine SvelteKit not becoming the #1 go-to in all cases in the near future—especially knowing it only came out of closed beta a matter of months ago.

The Svelte rocketship is a wonderful place to be. I encourage you to step aboard.